Geopolitical Potential

Thinking about history through physics

In geopolitics, absolute power doesn’t matter as much as relative power shifts between states. For instance, for much of the past forty years it was Japan and not China that was the second most powerful economy in the world. Japan became second in 1968 yet American alarm over Japan’s rise was limited to before roughly 1990, because this was the only period when Japan’s trajectory was on the rise relative to the US. From the 1990s, even though Japan remained number two, it ceased to be of any concern when it became clear that Japanese growth wouldn’t be enough to catch up to the US. After that, it didn’t matter whether they were second, third, or fourth.

Similarly today, it doesn’t matter so much that China is second as much as that its trajectory is rising relative to the US. Although China still remains behind the US in many sectors, it’s China’s meteoric rise relative to the US (and everyone else) over the past few decades that has caused instability in the postwar global order.

From a historical perspective, the Thucydides Trap best illustrates the importance of relative shifts in power. American political scientist Graham Allison coined this term to describe the tendency towards instability “when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power”. Allison used this concept to describe the US and China but this dynamic is visible throughout history. From Sparta being threatened by the rise of Athens to Germany and Britain before WWI. The German Empire never became as strong as Britain – for example, its navy never caught up to the British navy in size. Nevertheless, the British were clear that their relative advantage had to be maintained. This is why they introduced the two-power standard that the Royal Navy had to be at least as strong as the next two countries’ combined navies. In these cases, the relative shift in power is what disrupted the status quo.

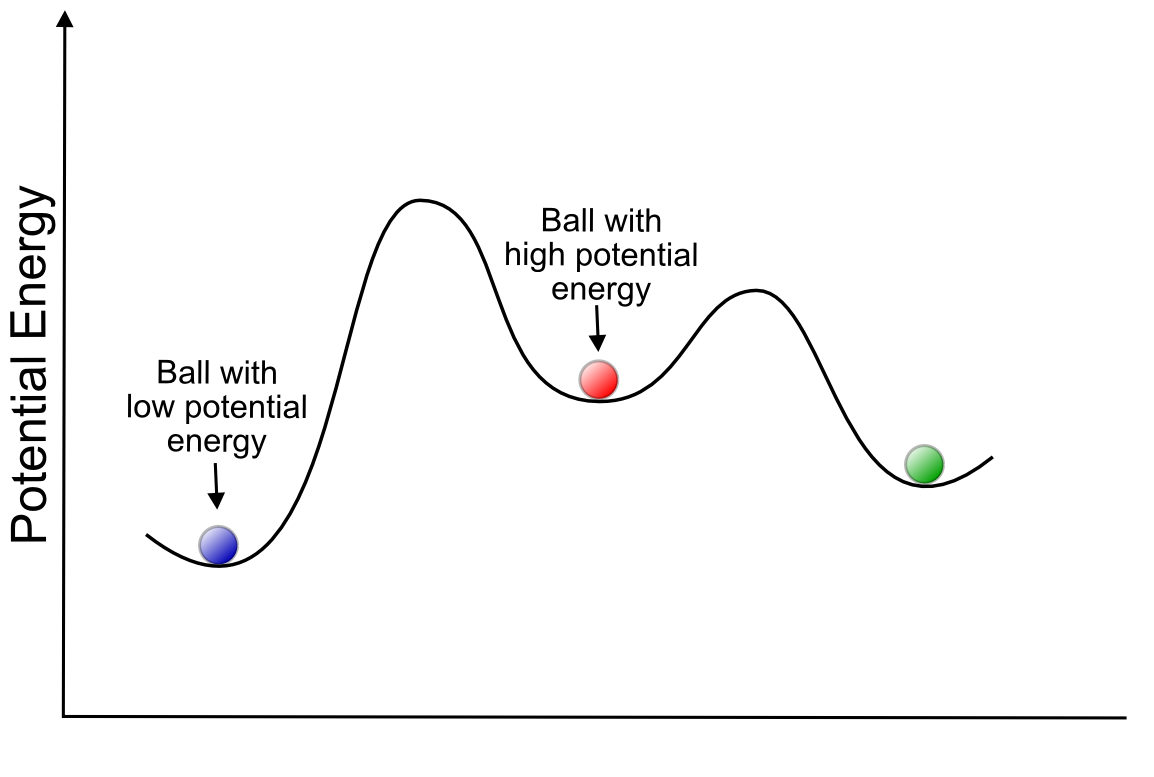

Us physicists can’t resist making physics analogies and there is one here too. We can compare relative shifts in the power of nations that cause global instability to the notion of potential energy and forces. The absolute value of an object’s potential energy doesn’t matter - it’s the relative difference of the energy at the start and end that matters. Forces are only generated when there is a change in the potential energy. More precisely: forces are the negative gradients of potential energies, and it is these forces that cause observable real world effects. Similarly, global instability arises when there is a change in what we could call a “geopolitical potential”. A country’s absolute power doesn’t matter as much as its power relative to others. A rising country climbs its geopolitical potential while a declining country falls down it, and these shifts cause the events that drive history like wars and revolutions. One might say heuristically that history is a function of the gradient of the geopolitical potential.

What influences the shape of this geopolitical potential? Long term impersonal forces like economic and demographic trends have to factor in. Shorter term forces like leadership must also play a role. One could come up with a whole array of factors and debate their relative weight. These factors then shape the landscape of minima and maxima of geopolitical potentials. It is along these slopes that countries shift up and down and so move history forward.